Side Effect Risk Calculator

What this tool does

This calculator helps you determine if your medication side effects are likely dose-related (Type A) or non-dose-related (Type B) based on clinical factors. It's designed to help you understand whether your symptoms might be predictable and fixable, or potentially dangerous and require permanent drug avoidance.

Risk Assessment Results

When you take a medication, you expect it to help - not hurt. But side effects happen. Some are predictable, like a headache from blood pressure medicine. Others come out of nowhere - a rash after one pill, even if you’ve taken it safely before. The difference between these two kinds of reactions isn’t just academic. It changes how doctors treat you, what tests they order, and whether you can ever take that drug again.

What Are Dose-Related Side Effects?

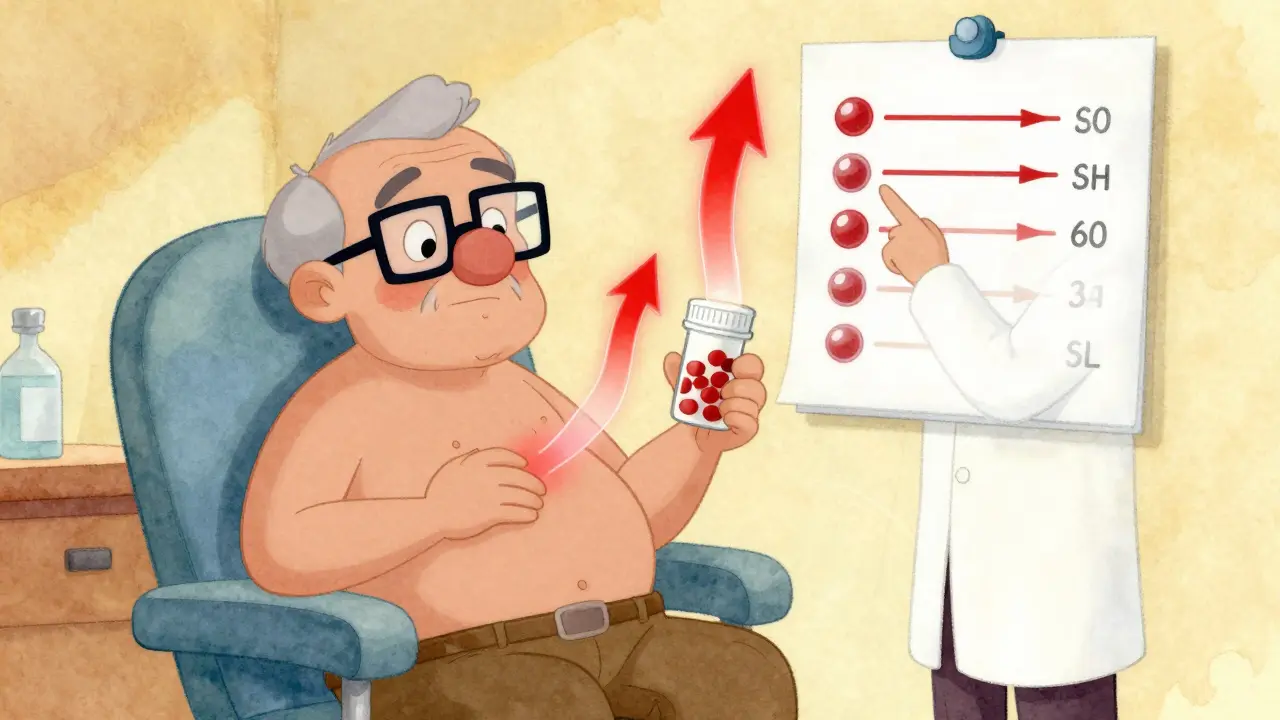

Dose-related side effects - also called Type A reactions - are the most common. They happen because the drug is doing exactly what it’s supposed to do, just too much. Think of it like turning up the volume on a speaker: the sound gets louder, but it’s still the same song. These reactions follow the law of pharmacology: more drug = more effect. And when that effect goes beyond the benefit, you get a side effect.

Examples are everywhere. Too much insulin? Blood sugar crashes below 70 mg/dL. Too much warfarin? Your INR spikes above 4.0, and you risk internal bleeding. An elderly patient on digoxin gets nauseous and sees yellow halos? That’s toxicity - not a new disease, just too much of the same drug. These reactions are predictable, measurable, and often preventable.

Drugs with narrow therapeutic windows are the biggest culprits. Digoxin’s safe range is 0.5 to 0.9 ng/mL. Above 2.0, you’re in danger. Lithium? 0.6 to 1.0 mmol/L is therapeutic. Go over 1.2, and you risk tremors, confusion, even seizures. These aren’t rare. In fact, about 80% of all adverse drug reactions are Type A. And they’re responsible for nearly 70% of emergency visits in older adults, especially from anticoagulants, insulin, and diabetes pills.

Why do they happen? Usually, it’s something outside the drug itself. Kidney function drops, so the drug builds up. A new antibiotic blocks the enzyme that breaks down your statin, making its levels jump fivefold. You forget to eat before taking metformin, and your stomach gets upset. These aren’t random. They’re clues - and they’re fixable.

What Are Non-Dose-Related Side Effects?

Non-dose-related side effects - Type B reactions - are the scary ones. They’re not about how much you took. They’re about who you are. Your immune system, your genes, your body’s odd quirks. These reactions can happen on the very first dose, even if you’ve taken the drug safely before. And they’re often severe.

Think anaphylaxis after penicillin. Stevens-Johnson syndrome from lamotrigine. Drug-induced liver failure from amoxicillin-clavulanate. These aren’t exaggerated versions of the drug’s action. They’re completely unexpected. Your body doesn’t just react too strongly - it reacts the wrong way.

One of the biggest surprises? These reactions aren’t always truly “non-dose.” Some people have a threshold - a tiny amount that triggers their immune system, while others can take ten times that and be fine. But because the threshold varies so wildly between people, it looks random. That’s why doctors say they’re “idiosyncratic” - meaning, unique to the individual.

Genetics play a huge role. If you’re of Asian descent and carry the HLA-B*15:02 gene, taking carbamazepine can trigger a life-threatening skin reaction. Testing for that gene costs about $215 - and prevents disaster. Same with abacavir: if you have HLA-B*57:01, you’re at high risk for a deadly hypersensitivity reaction. Screening for it cuts that risk from 5% to near zero.

Even though Type B reactions make up only 15-20% of all side effects, they cause 70-80% of serious hospitalizations and nearly all drug withdrawals from the market. Why? Because they’re unpredictable. No amount of monitoring can catch them before they happen. You can’t adjust a dose to avoid them. The only safe move is to stop the drug - forever.

Why the Distinction Matters in Real Life

Here’s where theory meets the clinic. A 72-year-old man on warfarin starts taking amiodarone for heart rhythm issues. Two weeks later, his INR is 8.2. That’s not a mistake. That’s a classic Type A interaction. Amiodarone blocks the enzyme that clears warfarin. The fix? Lower the warfarin dose and check INR every few days. He’ll be fine.

Now, a 28-year-old woman takes lamotrigine for epilepsy. She follows the exact titration schedule - 25 mg daily for two weeks, then 50 mg. On day 17, she wakes up with a painful rash that spreads like wildfire. Her skin blisters. Doctors diagnose Stevens-Johnson syndrome. No dose adjustment would have helped. No monitoring would have predicted it. She had to stop the drug immediately - and can never take it again. That’s Type B.

One is manageable. The other is permanent. And doctors have to know the difference fast.

For Type A reactions, the tools are clear: therapeutic drug monitoring (measuring drug levels in blood), adjusting for kidney or liver function, checking for drug interactions. Vancomycin? Keep trough levels between 10-20 mg/L. Phenytoin? Stay under 20 mcg/mL. These aren’t guesses - they’re science-backed targets.

For Type B, prevention is everything. Skin testing for penicillin allergy. Genetic screening before carbamazepine or abacavir. Graded challenges for patients with low-risk allergy histories. The American College of Clinical Pharmacy found that hospitals using these protocols cut major bleeding from warfarin by 35%. That’s lives saved.

What the Numbers Don’t Tell You

Here’s something most people don’t realize: Type A reactions cost the U.S. healthcare system $130 billion a year. They’re the reason so many older patients end up in the ER. But Type B reactions? They’re the reason lawsuits happen. The reason drugs get pulled. The reason pharmaceutical companies lose billions.

And here’s the irony: we’re getting better at predicting Type A. Machine learning models now spot them with 82% accuracy by analyzing EHR data - drug lists, lab results, age, kidney function. But Type B? Only 63% accurate. Why? Because they’re not about numbers. They’re about biology we don’t fully understand.

That’s why the FDA now requires pharmacogenomic info on 311 drug labels. And why 28 of those drugs require mandatory genetic testing before use. The future isn’t just about dosing right - it’s about matching the right drug to the right person before the first pill is swallowed.

What You Can Do

If you’re on chronic medication, ask your doctor:

- Is this drug known for dose-related side effects? If so, do I need regular blood tests?

- Are there any genetic risks I should be screened for before starting?

- What’s the first sign I should call you about - a headache, or a rash that spreads?

Don’t assume a side effect is normal. If you get a rash, swelling, fever, or blistering after starting a new drug - stop it and call your doctor immediately. Don’t wait. Don’t try to “tough it out.” That’s not bravery. That’s risk.

And if you’ve had a severe reaction before, carry a medical alert card. List the drug and the reaction. Even if you’re not sure if it was Type A or Type B - better safe than sorry.

The truth is, most side effects aren’t your fault. But understanding the difference between dose-related and non-dose-related reactions? That’s power. It helps you ask the right questions. It helps your doctor make smarter choices. And sometimes, it saves your life.

Are all side effects dose-dependent?

No. Most side effects - about 80% - are dose-related (Type A), meaning they get worse with higher doses. But about 15-20% are non-dose-related (Type B), caused by immune reactions or genetic factors. These can happen at any dose, even the first one, and aren’t tied to how much you took.

Can you prevent non-dose-related side effects?

Sometimes. For certain drugs, genetic testing can identify people at high risk. For example, testing for HLA-B*57:01 before giving abacavir prevents deadly hypersensitivity. HLA-B*15:02 screening before carbamazepine reduces skin reaction risk in Asian populations. Skin tests for penicillin allergy also help. But for many Type B reactions, there’s no way to predict them - so stopping the drug at the first sign of a serious reaction is critical.

Why do some people have side effects at low doses?

For dose-related reactions, it’s usually because their body processes the drug differently - slower kidney clearance, liver enzyme differences, or drug interactions. For non-dose-related reactions, it’s often due to genetics or immune system quirks. Some people have a very low threshold for triggering an allergic response - so even a tiny amount can cause a big reaction.

Are Type B reactions more dangerous than Type A?

Yes, in terms of severity. Type A reactions are more common but rarely fatal (under 1% mortality). Type B reactions are rare (15-20% of cases) but cause 70-80% of serious hospitalizations and have a mortality rate of 5-10%. They’re unpredictable, often irreversible, and require permanent drug avoidance.

Can you outgrow a non-dose-related side effect?

No. If you’ve had a true Type B reaction - like anaphylaxis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, or severe drug-induced liver injury - you should avoid that drug and similar ones for life. Your immune system or genetic risk doesn’t change. Re-exposure can be fatal. Even if you had a mild reaction before, never try the drug again without specialist supervision.