Gene therapy promises to fix diseases at their root-by changing your DNA. But behind that promise lies a hidden danger: how it interacts with the drugs you’re already taking. This isn’t just about side effects. It’s about unpredictable, sometimes deadly, changes in how your body handles medication. And the risks don’t disappear after a few weeks. They can show up years later.

Why Gene Therapy Isn’t Like Regular Medicine

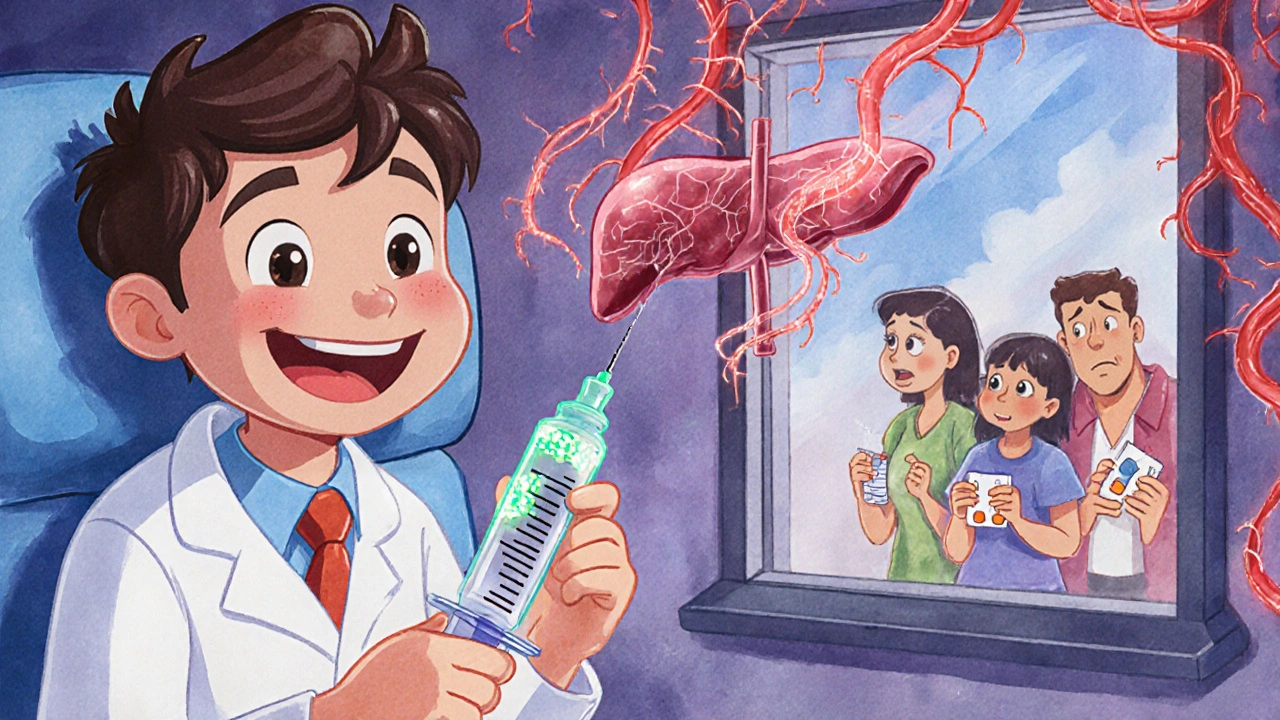

Most drugs work temporarily. You take a pill, it does its job, and your body breaks it down. Gene therapy is different. It’s meant to last. Some therapies insert new genes into your cells that keep working for years, even for life. That permanence is powerful-but it also means mistakes stick around. The most common tools for delivering these genes are modified viruses. Adeno-associated viruses (AAV), adenoviruses, and retroviruses are engineered to carry therapeutic DNA into your cells. But they’re still viruses. Your immune system sees them as invaders. And when that happens, everything changes. In 1999, an 18-year-old named Jesse Gelsinger died after receiving gene therapy for a rare liver disorder. His body mounted a massive immune response to the adenovirus vector. Within days, his organs failed. Autopsies showed his immune system had gone into overdrive-something that hadn’t been fully predicted in animal tests. That case changed everything. It proved that gene therapy isn’t just about the gene. It’s about the delivery system… and how your body reacts to it.When Your Immune System Rewires Drug Metabolism

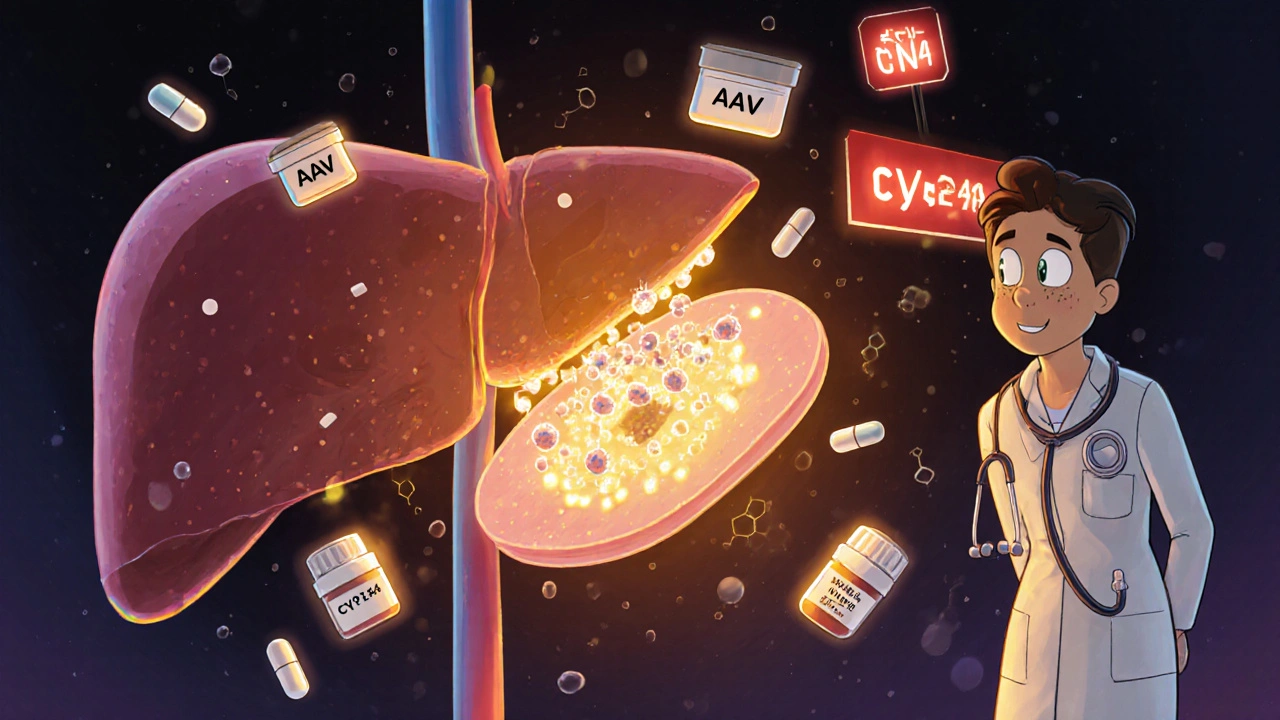

Your liver doesn’t just process alcohol or painkillers. It uses a family of enzymes called cytochrome P450 to break down over 70% of all prescription drugs. These enzymes are sensitive. Infections, inflammation, even stress can alter how fast or slow they work. Gene therapy triggers inflammation. Viral vectors activate toll-like receptors. Cytokines flood your bloodstream. That inflammation can turn P450 enzymes up or down-sometimes dramatically. A patient receiving AAV gene therapy for a muscle disorder might also be taking blood thinners, statins, or antidepressants. If the therapy suppresses CYP3A4, a key enzyme, those drugs could build up to toxic levels. If it boosts CYP2D6, the drugs might stop working entirely. There’s no way to predict this for every patient. Genetics, age, existing liver health, and even gut bacteria influence the response. Two people getting the same gene therapy, on the same drugs, could have completely different outcomes.Off-Target Changes and Hidden Drug Risks

Gene therapy isn’t always precise. Even the best vectors can slip into the wrong cells. That’s not just a problem for the intended target organ-it’s a problem for your whole system. Imagine a therapy meant to fix a heart condition accidentally modifies liver cells. Now those liver cells start producing a protein they never should. That protein could interfere with how your liver metabolizes drugs. Or worse-it could turn on a cancer gene. That’s what happened in early gene therapy trials for SCID-X1, a rare immune disorder. Five children developed leukemia because the therapy inserted the new gene next to LMO2, a gene that controls cell growth. The inserted gene accidentally turned LMO2 on. Cancer followed. These aren’t theoretical risks. They’ve happened. And they take years to show up. That’s why the FDA now requires 15 years of follow-up for therapies using integrating vectors-like retroviruses or lentiviruses. You can’t just check in after 30 days. You need to watch for decades.

Drug Interactions You Can’t Test for

Pharmaceutical companies test new drugs against hundreds of other medications. But gene therapy? There’s no playbook. There are no standardized drug interaction studies because the therapies are too new, too individualized. A patient might get gene therapy for Duchenne muscular dystrophy while taking corticosteroids to reduce inflammation. The therapy might change how those steroids are processed. But no clinical trial has looked at that exact combination. Even more troubling: gene therapy can affect cells that don’t even show symptoms. A therapy targeting the retina might accidentally alter gene expression in the brain. That could change how your brain responds to antidepressants or seizure medications. And you wouldn’t know until something went wrong.Transmission Risks: Therapy Spreading to Others

This one is strange, but real. Some gene therapies use live viral vectors that can be shed. That means the modified virus might be present in saliva, urine, or semen after treatment. In rare cases, it can spread to family members or caregivers. The FDA now requires companies to prove their vectors won’t transmit. But what if they do? A spouse or child who gets exposed to the therapy without consent could end up with altered genes. They’d have no medical history, no monitoring plan, no way to know what drugs are safe for them. This isn’t science fiction. It’s a documented concern in clinical trial protocols. And it’s one of the few situations in medicine where a treatment can accidentally be given to someone who never agreed to it.Who’s at Greatest Risk?

Not everyone faces the same dangers. Certain groups are more vulnerable:- Children: Their immune systems are still developing. They’re more likely to mount strong responses to viral vectors.

- People with pre-existing liver disease: Their livers can’t handle the extra stress from inflammation or altered metabolism.

- Those on multiple medications: The more drugs you take, the higher the chance of a dangerous interaction.

- Patients with autoimmune conditions: Their immune systems are already primed to react. Gene therapy can push them over the edge.

What’s Being Done to Fix This?

Regulators are trying. The FDA and EMA now require:- 15-year follow-up for integrating therapies

- Preclinical testing for immune response and off-target effects

- Clear labeling of potential drug interactions

- Strict protocols for managing concomitant medications during trials

What Patients Need to Know

If you’re considering gene therapy-or know someone who is-ask these questions:- What vector is being used? (AAV, adenovirus, lentivirus?)

- Is it integrating or non-integrating?

- What drugs am I taking now? Are they on the exclusion list?

- Will I need to stop any medications before treatment?

- How long will I need to be monitored? Who will track my drug levels?

- What happens if I get sick or need surgery later?

The Bottom Line

Gene therapy is revolutionary. It’s saved lives. But it’s not magic. It’s biology-and biology is messy. The interaction between gene therapy and drugs isn’t a minor footnote. It’s one of the biggest safety challenges we’ve faced in modern medicine. We’re learning. But we’re still flying blind in many ways. For now, the safest approach is caution: careful selection, full disclosure of all medications, and long-term monitoring. Because the risk isn’t just in the first month. It’s in the next 10 years.Can gene therapy change how my medications work?

Yes. Gene therapy can trigger immune responses and inflammation that alter how your liver processes drugs. This can make medications stronger or weaker than expected. For example, if your CYP3A4 enzyme slows down, blood thinners or cholesterol drugs could build up to dangerous levels. There’s no universal rule-each case depends on the vector, your genetics, and your current meds.

How long do I need to be monitored after gene therapy?

For therapies that integrate into your DNA-like those using retroviruses or lentiviruses-you’ll need monitoring for at least 15 years. This is required by the FDA because cancer or other late effects can appear years later. Even non-integrating therapies like AAV may need 5-10 years of follow-up due to long-term gene expression and immune changes.

Can gene therapy be passed to family members?

In rare cases, yes. Some viral vectors can be shed in bodily fluids like saliva or urine. While most modern therapies are designed to prevent this, regulators still require proof that transmission won’t occur. If it does, a family member could receive unintended gene therapy without consent, putting them at unknown risk-especially if they’re taking medications.

Are there any drugs I should avoid before gene therapy?

Yes. Immunosuppressants, corticosteroids, and certain antivirals may interfere with how well the therapy works. Others, like NSAIDs or statins, could increase inflammation or liver stress. Always provide your full medication list to your care team. Never stop or start a drug without their guidance.

Why don’t we have better drug interaction data yet?

Because gene therapy is too new and too personalized. Each therapy targets a specific gene in a specific patient. There aren’t enough patients yet to run large drug interaction studies. Plus, immune responses vary too much between people. Researchers are building databases to track these cases, but we’re still years away from reliable predictions.

Comments

Victor T. Johnson

Gene therapy is basically playing god with a broken toolbox and hoping the house doesn't burn down 🤡

They slap a virus in you and act like it's a software update. But your body ain't a Macbook. It's a warzone with hormones and cytokines throwing Molotovs. And now you're stuck with a permanent glitch that might turn your statins into poison. No thanks.

On November 16, 2025 AT 03:17

Nicholas Swiontek

This is why we need better communication between specialists. I work with patients on gene therapy and they’re often on 5+ meds. We’re winging it. But I’m glad someone’s finally talking about it. Let’s get a registry going. Real-time tracking. No more guessing.

❤️

On November 17, 2025 AT 15:56

Robert Asel

It is imperative to underscore that the current regulatory framework, while commendable in its intent, remains fundamentally inadequate to address the systemic, multi-layered pharmacogenomic risks inherent in viral vector-mediated gene transfer. The absence of longitudinal, population-scale pharmacokinetic modeling constitutes a glaring epistemological void in contemporary translational medicine.

On November 18, 2025 AT 02:22

Shannon Wright

I’ve seen families torn apart by this. One mom got gene therapy for a rare disease, and six months later, her teenage son got sick from a drug he’d been on for years-doctors couldn’t figure out why. Turns out, her therapy changed his liver enzymes through a shared environment. It’s not just about the patient. It’s about everyone in your household. We need mandatory family counseling before treatment. Not optional. Mandatory. And we need to stop acting like this is just ‘science fiction’-it’s happening now.

Let’s not wait for another Jesse Gelsinger.

On November 19, 2025 AT 00:12

vanessa parapar

Oh please. You think this is new? People have been dying from drug interactions since the 1950s. This is just the latest flavor of fear-mongering. If you’re scared of your meds, don’t take them. Simple. Also, AAVs don’t shed. That’s a myth from 2003. Get your facts right before you scare people.

On November 20, 2025 AT 23:23

Ben Wood

...and yet... nobody... talks about... the fact... that... the FDA... is... being... Lobbied... by... biotech... giants... who... want... to... fast-track... this... stuff... because... they... know... the... long-term... data... doesn't... exist... and... they're... betting... on... amnesia... and... regulatory... capture... and... you... know... what... happens... when... you... bet... on... amnesia...?... People... die... and... then... we... get... a... press... release... about... 'unexpected... but... acceptable... risk'... and... move... on...

...this... is... how... we... lose... our... souls... one... clinical... trial... at... a... time...

On November 22, 2025 AT 11:05

Sakthi s

Good post. Stay safe. Monitor. Ask questions. Don’t rush.

On November 23, 2025 AT 19:56

Rachel Nimmons

Did you know the military funded early AAV research? They wanted gene-edited soldiers. What if this isn’t just about medicine… what if it’s about control? Who’s tracking the data? Who owns your edited genome? And what happens when insurance companies find out your CYP3A4 got permanently downregulated? They’ll drop you faster than a bad stock.

On November 25, 2025 AT 10:20

Abhi Yadav

We’re all just temporary vessels for DNA code anyway… the real question isn’t whether gene therapy alters drug metabolism… it’s whether we’re still human after we’ve been rewritten… 🤔

On November 26, 2025 AT 00:36

Julia Jakob

so i had this friend who got gene therapy for spinal muscular atrophy... she was on blood thinners... and then six months later she started bleeding out for no reason... they didn't connect it until her cousin, who's a pharmacist, asked 'wait... did she get a viral vector?'... yeah... turns out the therapy knocked out her CYP2C9... and no one told her to stop the warfarin... she almost died... and now they're all like 'well... it's rare'... yeah... for now...

and no one's keeping a public list of these cases... because then people would stop signing up... and the money would stop flowing...

On November 26, 2025 AT 03:43

Robert Altmannshofer

Look, I get the hype. Gene therapy is wild. But this post? It’s the reality check we need. I work in a clinic where half the patients are on statins, antidepressants, and now we’re throwing in AAVs like it’s a smoothie. We don’t have the tools to predict what happens. We’re just watching. Waiting. Praying. And honestly? That’s terrifying. We need real-time monitoring apps. Not just blood tests once a year. We need alerts. Like ‘Your CYP3A4 is down 60%. Stop taking simvastatin.’ Until then, we’re all just guessing with someone else’s life.

On November 26, 2025 AT 08:28

Kathleen Koopman

Wait, so if someone gets gene therapy and then gets pregnant, could the virus affect the baby? Or if the mom sheds the vector and the baby gets exposed? 😳 Is that even studied? I need to know before I consider this for my kid.

On November 27, 2025 AT 11:15

Nancy M

In India, we have a different problem: access. Even if we understood the interactions, most patients can’t afford the follow-up tests. We don’t have the infrastructure for 15-year monitoring. So we give therapy and hope. That’s not ethics. That’s desperation. And we’re not alone. This isn’t just a scientific problem-it’s a global justice issue.

On November 28, 2025 AT 02:52

gladys morante

They’re lying. They always lie. They said the same thing about thalidomide. About Vioxx. About opioids. Now they’re saying gene therapy is safe. But they’re not testing the long-term effects because they know the truth: it’s a bomb with a slow fuse. And they’re betting you won’t live long enough to blow up.

On November 29, 2025 AT 22:08

Precious Angel

Oh, so now we’re supposed to trust Big Pharma to tell us when their gene therapy is safe? Please. The same companies that hid the opioid crisis are now selling you a DNA edit that could turn your liver into a drug-processing minefield. And you’re supposed to sign a consent form that says ‘I understand this might kill me in 5 years’? No. No. No. This isn’t medicine. It’s a corporate experiment with your genome as the lab rat. And if you’re lucky, you’ll be the one who dies quietly while they patent the next version.

On December 1, 2025 AT 21:53

Melania Dellavega

I’ve sat with families after gene therapy. The hope is beautiful. The fear is real. But what breaks my heart is when they say, ‘We didn’t know it could affect his asthma meds.’ Or ‘We didn’t know she’d need to stop her antidepressants for a year.’ We don’t have enough time with patients. We don’t have enough training. And we’re not building systems to catch these things. It’s not about fear. It’s about responsibility. We owe people more than a brochure and a handshake.

On December 2, 2025 AT 20:27

Bethany Hosier

According to the CDC’s 2023 Surveillance Report on Gene Therapy Adverse Events (GTAE-2023), Section 4.2, Subsection C: ‘Vector Shedding in Household Contacts,’ there were 17 documented cases of non-consensual gene transfer among cohabiting individuals, with 3 resulting in seroconversion and altered cytochrome P450 activity in the exposed, non-treated individuals. This data, while statistically rare, constitutes a Category 1 Bioethical Emergency under WHO Guideline 7.1b. I urge all regulatory bodies to immediately mandate genetic screening for all household members prior to treatment initiation.

On December 3, 2025 AT 09:22