When you pick up a prescription, you might assume the pharmacist will give you the cheapest version of your medicine - and in many places, they have to. But in others, they can only offer it if you say yes. This isn’t about pharmacy policy. It’s about state law. And the difference between mandatory and permissive substitution can change how much you pay, whether you stick to your treatment, and even how safe your medication is.

What’s the real difference between mandatory and permissive substitution?

Mandatory substitution means the pharmacist must swap your brand-name drug for a generic version - unless your doctor specifically says not to. Permissive substitution means the pharmacist can swap it, but only if they choose to - and sometimes only if you agree.

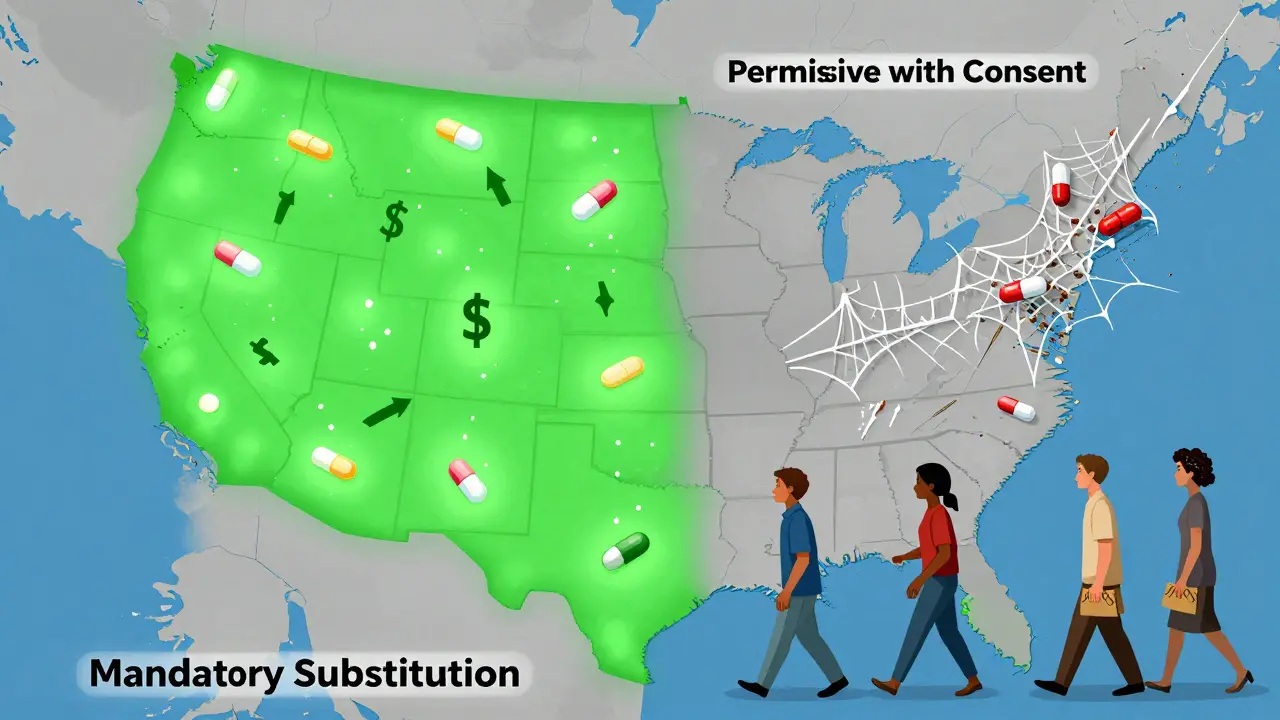

This isn’t a minor detail. It’s a legal requirement written into each state’s pharmacy code. In 19 states - including Alabama, Colorado, Maine, and West Virginia - pharmacists are legally required to substitute generics when they’re available and therapeutically equivalent. In the other 31 states and Washington, D.C., substitution is optional. That means in those places, even if a generic is cheaper and just as effective, the pharmacist might still hand you the brand-name pill - unless you ask for the generic.

The system was set up by the federal Hatch-Waxman Act in 1984, which created the pathway for generic drugs to get FDA approval. But it left the actual substitution rules to the states. That’s why today, you could get a generic in New York and still get the brand in California - even if you’re on the same prescription.

Why does patient consent matter so much?

It’s not just about whether substitution is required. It’s about who gets to say yes or no.

Seven states - plus Washington, D.C. - require explicit patient consent before a generic can be swapped in. That means the pharmacist has to ask you, “Do you want the cheaper version?” and get your answer before they fill it. Sounds fair, right? But here’s the catch: most people don’t know what they’re being asked. They sign a form, hear “Do you want to save money?” and say yes without understanding the implications.

Studies show this one rule makes a massive difference. In states that don’t require consent, 98% of prescriptions for simvastatin (a common cholesterol drug) were filled with generics within six months of the brand losing exclusivity. In states that did require consent? Only 32% were.

That’s a 66-percentage-point gap - just because one extra step was added. And it’s not just about cost. People who don’t get the generic because of consent rules are less likely to refill their prescriptions. They think the brand is better. Or they don’t understand why the pill looks different. Or they’re confused by the paperwork. The result? Worse health outcomes, higher hospitalization rates, and more money spent overall.

How do states decide what drugs can be substituted?

Most states rely on the FDA’s Orange Book - the official list of drugs deemed therapeutically equivalent. If a generic is listed there, it’s considered interchangeable. But not all states follow the same rules.

Some use positive formularies - meaning they only allow substitution for drugs they’ve specifically approved. Others use negative formularies - banning substitution for certain high-risk drugs like seizure medications or blood thinners. Most, however, just follow the Orange Book and let pharmacists make the call.

But here’s where it gets messy: some drugs have a narrow therapeutic index. That means even a tiny difference in how the drug is absorbed can cause serious side effects. For drugs like warfarin, levothyroxine, or phenytoin, many states require extra steps - like physician approval or special labeling - before substitution is allowed. Even in mandatory states, pharmacists often hesitate to swap these drugs unless they’re absolutely sure it’s safe.

And prescribers? They can block substitution by writing “Dispense as Written” or “Brand Medically Necessary” on the prescription. But in some states, they have to give a reason. In others, they can just check a box. That inconsistency makes it hard for pharmacists to know what’s allowed - and for patients to know why they’re getting one pill instead of another.

What happens with biologics and biosimilars?

It’s not just about pills. Biologics - complex drugs made from living cells - are the most expensive drugs in the system. Think Humira, Enbrel, or insulin analogs. Their generic versions? Biosimilars. They’re not exact copies, but close enough to be considered safe and effective.

Here’s the kicker: 45 states treat biosimilars completely differently than regular generics. They require extra steps - like mandatory physician notification, detailed recordkeeping, or even patient consent - before a biosimilar can be swapped in. Only nine states and D.C. treat them the same way as small-molecule generics.

Why? Because biologics are more complex. There’s real concern about immune reactions if you switch back and forth between products. But the data shows that for many biosimilars, switching is safe. Still, states are being cautious. And that caution comes at a cost. In 2020, biologics made up just 2% of prescriptions but 42% of Medicare Part D spending. If substitution rules were streamlined, billions could be saved.

Who’s affected the most by these laws?

Low-income patients on Medicaid feel it the hardest. A 2011 study found that in mandatory substitution states, generic use for simvastatin was nearly 20% higher than in permissive states. That’s not just a number - it’s thousands of people who can afford their meds because they’re not paying $300 for a brand-name pill when a $50 generic exists.

But it’s not just about money. It’s about access. In states with permissive substitution and consent requirements, pharmacists often don’t even offer the generic unless asked. Patients who don’t know to ask? They get the brand. And if they’re elderly, non-English speaking, or have low health literacy? They might never realize they’re being overcharged.

Pharmacists are caught in the middle. In 24 states, they have no legal protection if something goes wrong after a substitution. That means even if they follow every rule, they could still be sued. So many avoid substitution altogether - especially for high-risk drugs - just to stay safe.

Why are these laws changing - and where are they headed?

The number of mandatory substitution states has grown. In 2014, 14 states required it. By 2020, it was 19. That’s a clear trend: lawmakers are realizing that letting pharmacists swap generics saves money and improves care.

But as new drugs come out - especially complex ones like gene therapies and combination products - the rules are getting more complicated. Some states are starting to require electronic notifications, digital consent forms, and real-time tracking of substitutions. Others are creating special rules for mail-order pharmacies or for patients in nursing homes.

What’s next? More states will likely move toward mandatory substitution - but with smarter safeguards. Instead of blanket consent rules, they may require education: a short video, a printed fact sheet, or a pharmacist-led explanation. The goal isn’t to block substitution. It’s to make sure patients understand it.

What should you do as a patient?

Don’t assume you’re getting the cheapest option. Always ask: “Is there a generic version?” Even in mandatory states, pharmacists sometimes don’t switch if the brand is on sale or if the prescription doesn’t clearly allow it.

If you’re on a high-risk drug - like a blood thinner or thyroid medicine - ask your doctor to write “Dispense as Written” if you’re concerned about switching. But if you’re on a routine medication like statins, blood pressure pills, or antibiotics, don’t hesitate to request the generic. It’s not just cheaper - it’s just as effective.

And if your pharmacist doesn’t offer the generic - even in a mandatory state - ask why. It might be a mistake. Or it might be that your state still has outdated rules. Either way, knowing your rights can save you hundreds a year.

What’s the bottom line?

State laws on generic substitution aren’t just legal technicalities. They’re powerful tools that shape health outcomes. Mandatory substitution without unnecessary consent requirements leads to higher generic use, lower costs, and better adherence. Permissive substitution with consent requirements slows things down - and costs lives.

The system isn’t broken. It’s just uneven. And until all states align around simple, evidence-based rules, patients will keep paying more - and getting less - just because of where they live.